IAN: Since September 11th, you've spent most of your time traveling around America, lecturing about America's actions in Afghanistan. What sort of response have you been getting?

HOWARD: No matter what part of the country I've been in, the reaction to my criticism of the war has been overwhelmingly positive. It's interesting, because President Bush is still getting something like ninety-percent support ratings in the newspapers. But public opinion polls are very deceptive. Somebody sticks a microphone in front of a person and says, "Do you support the President?" It's been very difficult to be a dissenter. Not only difficult, but frightening. I know of people who have been visited by the FBI just for having an anti-Bush poster in their apartment, or for making an anti-Bush remark in a sports club.

IAN: Wow. Add. GET MORE FROM IAN.

HOWARD: Also, many people simply don't have sources of information other than what they see on TV. Without information, they have no basis for dissent. I only lecture for an hour, but I've come to the conclusion that as soon as you remind people about the history of American foreign policy, they begin to rethink their initial acquiescence.

IAN: I was amazed by the Super Bowl halftime show this year, with all its flag-waving and military imagery.

HOWARD: The scariest part of it is that the government and the media want to raise a new generation to believe that the highest form of heroism is military.

IAN: You've devoted your career to questioning everything about the way that history is taught. Who have been some of the particularly compelling figures for you?

HOWARD: Eugene Debs, Mother Jones, Clarence Darrow ...

IAN: It makes a lot of sense that you'd be interested in people like that. But which figures on the other side of the fence have been especially interesting to you?

HOWARD: Interesting? [laughs] I'm always interested in figures who have been valued as great American heroes but who seem more like villains to me. Theodore Roosevelt is interesting from that point of view. He's always hailed as one of the great presidents, but to me he was a racist, an imperialist, a militarist and a lover of war.

IAN: "Speak softly and carry a big stick." Are there any particular episodes that you can tell me about?

HOWARD: He supervised the war in the Philippines, in which the United States Army was fighting against the indigenous independence movement. He was Vice President when the war began, but became President in 1901 when McKinley was assassinated. There were massacres and atrocities perpetrated by the American army, and Roosevelt approved of all of them anywhere from five hundred thousand to one million Filipinos were killed. In 1906, about six hundred Muslim Filipinos were massacred on one of the southern islands. They were virtually unarmed the men just had spears. The American army moved in and killed all of them men, women, and children. Afterwards, Roosevelt sent a telegram of congratulations to the commanding officer for this "military victory." Roosevelt was also responsible for creating the Republic of Panama. Colombia, which owned Panama, refused to sell it to the U.S. So Roosevelt just took it by force. Very early on, I came to believe that his stature as one of the great American presidents was undeserved.

IAN: I guess that when a component of fiction is added to history, it requires false heroes.

HOWARD: Right. One of the things I want to do is to create a new set of heroes. Instead of Theodore Roosevelt, let's have Mark Twain, who protested against Roosevelt's policy in the Philippines. Or instead of Woodrow Wilson, who was a racial segregationist and who got us into World War I, I would suggest Helen Keller. She protested against World War I. Instead of Andrew Jackson, let's have Osceola, the leader of the Seminoles, who was fighting for the survival of his people against the American army at the time of what is erroneously called "Jacksonian Democracy."

IAN: Who is a nefarious figure from more recent history?

HOWARD: Kissinger is the Machiavelli of our time. He was ruthless in the policies he advocated, most notoriously in Vietnam and in Cambodia. Kissinger also had a lot to do with the institution of a military dictatorship in Chile. Yet he is seen as an elder statesman he's called on for advice, he's put on television again and again. He's the contemporary equivalent to somebody like Roosevelt or Andrew Jackson.

IAN: Tell me, how did history come to be your passion?

HOWARD: Well, I didn't go to college until I was twenty-seven years old. I worked in a shipyard for three years. I was in the Air Force. So by the time I began to study history in college, I had a certain class consciousness. I grew up in a working-class family and saw how hard my father and mother, and so many people around me, worked and how little they had to show for it. I didn't grow up with a romantic notion of the American economic system and how wonderful it is. I never thought, "If you only work hard, you'll become successful and prosperous." It was obvious that nothing could be more untrue.

IAN: What was your position in the shipyard industry?

HOWARD: I was an apprentice shipfitter in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. We built battleships and landing ships. While I was there, I got involved with organizing the young shipyard workers. I suppose I learned from that the necessity for people who don't have any power in the workplace to organize to change their conditions.

IAN: Was there a union already in place when you began working there?

HOWARD: There were many craft unions, which admitted only certain skilled workers. But the so-called unskilled workers, like the riveters, the welders, the burners, and the apprentices, were not allowed into those unions.

IAN: Directly from the shipyard, you joined the Air Force. Were there parallels there in terms of class and skilled versus unskilled workers?

HOWARD: There's no society more divided along class lines than the military. You're either an officer or an enlisted man. I experienced both. When I became an officer, I saw that I had suddenly moved up into the aristocracy. I was wearing fine clothes, eating good meals, and being housed in a nicer way very different from when I was a private in basic training at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri. When we headed overseas, we went in a huge passenger ship, the Queen Mary, which had been converted for troop use. The officers ate in a magnificent dining room. The enlisted men ate the usual grub in a huge mess hall. In the midst of a war, with the constant threat of submarines and torpedoes, we had these liveried waiters and chandeliers.

IAN: Did you find that most of the people who rose in rank along with you assumed these privileges unquestioningly? Were you able to express your own opposition in any way?

HOWARD: One thing about the military is that you're indoctrinated not to question anything. But there were ways I could personally oppose it. In England, when a movie was shown on base, there would be a short line for the officers and another longer line for the enlisted men. I'd get the enlisted men that I knew to come with me over to the officers' line. In my crew, the officers fraternized with the men. It was frowned upon by the higher-ranking officers, but we kind of ignored them and did what we wanted to.

IAN: Those small gestures can have a lot of resonance. Class barriers seem to have been a focal point for you since you were very young.

HOWARD: When I began to study history, it was clear to me that from the time the first settlers arrived in North America, we had distinct classes. There were people with enormous grants of land, poor white people who had no land, white people who were servants, and black slaves. America has always been a country of rich and poor, landlords and tenants, masters and slaves. When we set up the Constitution, it reflected that.

IAN: Well, the Constitution was drawn up by the most privileged people in our society.

HOWARD: All you have to do is look at the effect of something like Shea's Rebellion in 1786, in which thousands of western Massachusetts farmers fought against the high taxes and the legislative edicts coming out of Boston. The next year, when the Constitutional Convention gathered in Philadelphia, they made sure to set up a strong government that would be able to handle rebellions and slave revolts and, in effect, take care of the interests of the wealthy. Essentially, the political and legislative history of this country is a history of wealthy people and corporations passing the kinds of laws that will favor them and maintaining the class system that we have always had in the United States.

IAN: How did your service in World War II shape your outlook? I know you were a bombardier.

HOWARD: There was a very powerful moral element in World War II, because we were fighting against fascism. Nevertheless, after I got out and contemplated my own missions, as well as what we had done to the civilian populations of places like Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Dresden, it became clear to me that "The Good War" was very complicated. The good guys behaved like the bad guys, and atrocities were committed by both sides. War corrupts everybody, and ultimately, it doesn't solve fundamental problems. After the war, sure, Hitler was gone, and the Japanese empire was gone. And yes, you could say something useful had been accomplished in getting rid of those regimes. But at the same time, fifty million people were dead. The world was not free of war, not free of militarism, fascism, imperialism, or racism. Now we had two superpowers building up atomic arsenals and the gap between rich and poor in the world growing and growing. I came to the conclusion that war cannot be a solution. If we have problems in the world, tyranny, aggression, whatever it is, we are going to have to use our ingenuity to figure out ways of solving those problems without killing millions of people.

IAN: When you were discharged from the army, you went to school on the GI Bill. I've heard that most of the GI's who went on to school were white.

HOWARD: As you know, it was a segregated army. But there were a lot of black soldiers in World War II, many of whom had been drafted. It's undoubtedly true that more whites took advantage of the GI Bill because even with the help of the bill, you couldn't afford school if you were really poor. Besides, at that time many blacks didn't even have a high school education, so they couldn't qualify to go to college. But there were millions of white, working class guys who went to college and then moved up into the middle class. This complicated the class structure of the United States by augmenting the buffer between the very poor and the very rich, which is the role that the middle class has always served in this country.

IAN: It also helped create the myth that we're all middle class.

HOWARD: Class is just not addressed in the United States. The pretense is that we're all one big happy family. The government uses language about representing "the national interest." This assumes that we all have the same interests you know, that Exxon and I have the same priorities, or that the government and I have the same desire to go to war. I'm suspicious of terms like "national security" or "national defense," which try to envelop the whole population within one common position which doesn't really exist.

IAN: I heard there's a film project in development, based on A People's History of the United States.

HOWARD: HBO has taken an option on the book, and scripts are being written. Ben Affleck, Matt Damon, Chris Moore, and I are executive producers. It's still in the early stages, but if HBO goes through with the project, it will be an extraordinary statement for a major network to make.

IAN: Going back to the situation with Afghanistan, do you see it as an extension of the Crusades?

HOWARD: While Bush regretted using the word "crusade," this conflict does take on the nature of a religious war. At this point, patriotism replaces Christianity as the motivation for the war, as the emotional unifier. But the psychology of the crusade is there, in that we are all united in the drive to end terrorism. And just as the Crusades were based on the impossible objective of Christianizing the world and ridding the world of infidels, ending terrorism is also an impossible objective that spurs us on and on. So you have Bush promising an endless war.

IAN: It's even more extreme than the Cold War. The government will need to manufacture more arms.

HOWARD: That's right. It's unlike past wars where the government promised light at the end of the tunnel. During World War II, they rushed to assure people, "This war isn't going to last long." During Vietnam, they said, "The boys will be home by Christmas." But the war on terrorism will go on and on. That's a frightful prospect, because it gives the government the right to curb civil liberties, and to take the wealth of the country and divert it into ever larger military budgets. This means there will be more profits for all the corporations who do work for the military. We're at a very dangerous point in American history.

IAN: So what is the light at the end of the tunnel, based on where we stand now?

HOWARD: I think there will be a recognition that terrorism will not be ended by war. With foreign policy issues, it's very easy to deceive the public. The government can tell us anything, and it's hard to check up on it. I think it's very important for people to seek out new sources of information, to read literature that doesn't come from the government. Read the alternative publications, listen to alternative radio. Go on the internet and find out as much as you can. Go to the library and read and read and read. Because somehow we must wake up from the great sleep that the government's propaganda machine is putting us in. It's going to take a lot of work on our part, but I have a certain confidence. Going around the country, I see how many good people there are, people with good values, people who want equality and don't want war. I have the feeling that good sense is bubbling just under the surface. That's my hope that the people will learn, and common sense will prevail.

|

|

|

|

|

|

©

index magazine

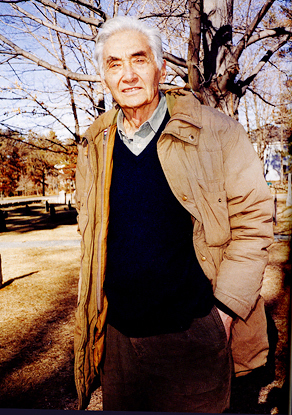

Howard Zinn by Tod Papageorge, 2002 |

|

©

index magazine

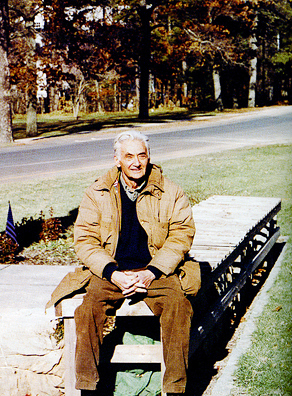

Howard Zinn by Tod Papageorge, 2002 |

|

|

| |

|

|

|