|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Read Bjork's2001 interview with Juergen Teller from the index archives. |

|

|

Kathleen Hanna discusses writing and making music in this interview from 2000 with Laurie Weeks. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Isabella Rossellini spoke with Peter Halley in this 1999 interview. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alexander McQueen's 2003 interview with Bjork. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

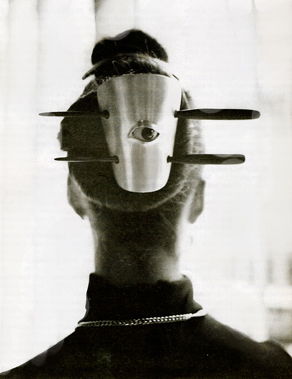

| Isabel Toledo,1997

WITH MARY CLARKE

PHOTOGRAPHED BY ANNETTE AURELL |

One time on the subway, I stared at designer Isabel Toledo and her artist husband Ruben all the way from Astor Place to Grand Central. You would too. They are so tiny and glamorous—Isabel with her butt-length, jet-black hair, and Ruben looking like a younger, thinner Marlon Brando. Isabel was wearing those classic 13-button wool sailor pants, the ones that no one was wearing at the time. A few months later, I'm at one of Isabel's shows and see that she's been inspired to do sailor-pant skirts. (Imagine a to-the-floor navy wool skirt with the same lace-up back and 13-button front as the pants—so beautiful!) Cheap copyist that I am, I went and bought my own sailor pants, slit the seams open and start pinning the whole mess into what I hoped would be a divine new skirt just like Isabel's. What a disaster. Ill-fitting, stiff, not at all flattering, the failed home-ec project still hangs in my closet, probably moth-eaten by now. I hoped to discover the secret to sailor-skirt success by hanging around Isabel's atelier for an afternoon.

MARY: I'm looking at what you're wearing, and it's a blouse and it's got this collar, but it's also got this other thing … (Isabel turns around to show me the back, where what appeared to be an undercollar in front flows into the body of the garment). Oh! See, I would never have guessed that that was going on in the back. It looks like a double collar from the front.

ISABEL: It's not. This is just a classic collar.

MARY: Your clothes are very organic.

ISABEL: Yes, I'm definitely not ornamental. Anything like this, which you think, "Oh, another collar" — it's not ornamental. It comes from somewhere. There's got to be a reason for it to be born, I always say. It isn't about the outside finished product. I never look at things flat. It's always so 3-D. I tell Ruben, "I want the fabric to do this. "I draw with my hand.

RUBEN TOLEDO: Isabel works very much like a sculptor would work. We never start with a theme, just with a feeling she wants, and it goes from there. Look at these blouses: they're all made from one piece of fabric. What's amazing is they're all like jellyfish — the way you can see the inside. Look at the sleeve, how it just spills out and becomes its outside. It's hard to communicate, though, because most people in the fashion world speak this language, like: we're doing tuxedoes, we're doing sailors.

ISABEL: How do you explain a jellyfish?

MARY: When I saw your sailor-pant skirts, I was, "Oh that's really good, I'm sure I can make one of those myself." And I couldn't get it right. I went and bought some sailor pants and still have the seams all ripped open and pinned together.

RT: Actually, that was the season all the trousers had the curved seams. Like, down the center-back. And then, the seam would come up and travel and cross the front and go back the other way. So it was this incredible arc.

MARY: No wonder mine didn't work—the seams were too straight. So how did you get started?

ISABEL: My first show was in '86. But even before that I was selling to Bendel's and Patricia Field. Actually, the first thing I did was a concession at Fiorucci. It was a little collection made out of burlap. Burlap lined in gauze. So I was selling to Fiorucci, to Patricia Field. And then I got a write-up in Women's Wear Daily and they wanted to know when my next collection was going to be presented. Someone from there contacted us and asked us the whole deal: When do you do your shows? So we figured OK, what month is that? OK, that's when we'll have our show. It was such a learning experience. You know, it's the only way — you just push on when you don't know.

MARY: So where was your first show?

ISABEL: On 57th Street and Fifth Avenue, in a shoe showroom. We rented a little space and about 50 people showed up. All the top people. I guess the Women's Wear Daily write-up got everybody there.

MARY: Correct me if I'm wrong, but it seems like your early pieces were almost homemade-looking.

ISABEL: Very. More like me-made. I made everything. Mama-made, as I say. I'm a technician. I experimented with patterns, and my early stuff was very origami, like lanterns. I experimented with organic shapes and then draped on the body. So if you look at a pattern, it was like a kite, then it was put together almost like origami. That's how it started. Ruben went, sold the line, came back. Sold it right out of my closet. We got married, we needed to make money, we moved to New York City. Ruben said: OK, we're going to start a business.

MARY: Where did you two meet?

ISABEL: We met in West New York, in high school. Memorial High School. In Spanish class. We're from two different parts of Cuba. He's from Havana, I'm from the countryside. I was eight when I moved here. Ruben was five. So we met in high school. Didn't date. Left school, dated afterwards. We were the best of friends in school.

MARY: And did you go to art school after that?

ISABEL: Ruben went to the School of Visual Arts and I went to Parsons. But we were dating already … that year right after high school. It was kind of natural, the whole thing.

MARY: And you two work really closely.

ISABEL: Very. You can't separate it. We discuss everything. (Isabel shows me stacks of drawing notebooks.) We have God knows how many books, they're like diaries. And his projects are in it. My projects are in it. My clothes. I talk about his work, he talks about mine. He draws everything, he schedules it all.

MARY: So you learned pattern making and all that at Parsons?

ISABEL: Yes, but I knew it all before I went to school. I actually learned from Vogue Patterns. Then little by little you learn the industry of it. You go from mama-made to industry-made. I used to line denim with satin. Beautiful different-colored satin. I sold that to Bergdorf Goodman. That was my first delivery. I remember they were very excited because they had a 75 percent sell-through in, like a month.

MARY: Is that really good?

ISABEL: Yes. It stamps you. They don't forget. But of course, everybody changes in the industry. Buyers change, presidents change … In '87 things totally dropped.

MARY: I read somewhere that you didn't sell retail for about three years.

ISABEL: Yes. When I started it was wonderful, but by the end of the '80s stores were just not buying. I'm a small little peanut. This little number here, next to Donna Karan's company, means nothing. I always sold in Japan, so that kept me going.

RT: You do get lost in the shuffle, unfortunately, but the good thing is we have these great loyal private customers. Some are like 60 and 70 years old. We've known them since 1985, and they keep coming back for more. Usually they'll have their same dress remade in wool jersey or something new. And then they'll buy something new. That's when you know clothes are good. They have a lifespan. And it's usually not young women who get it. It's usually older women, which is kind of great.

ISABEL: They've known quality. They've been exposed to design. Being able to handle clothes. Not "Just give me a T-shirt."

MARY: So did these women first discover you at Bergdorf Goodman?

ISABEL: No, a lot of the customers came from when I was at the Costume Institute at the Met.

MARY: what were you doing there?

ISABEL: Restoring.

MARY: Oh, I didn't realize you had done that.

ISABEL: I was in school. Diana Vreeland was still there. That was a great experience, to be surrounded by all those amazing clothes.

MARY: Did you pick up any special techniques?

ISABEL: Sure — the art of hardly touching the fabric when you stitch. And to see all the possibilities, because nowadays it's just — seams. You're so limited. There, you realized all that goes into a garment, and that it's OK to put it all in there. There's so much work that goes in.

MARY: What were some of your favorite pieces to look at?

ISABEL: Oh, Balenciaga was the best. That was so amazing. And Vionnet. And Charles James. But you know, it's not about one person. It's like I wouldn't even see the label. It was that cut, that mathematic equation. You know, those are thinkers who spent time asking "What's the best way to do this? What's the best, the smartest construction for something?" Not just, cut it up sew it up. That's easy.

MARY: Was everything hand-stitched?

ISABEL: Yes. And I took from that. I came from that world of construction and took it to the modern times, because I love machines. There's not one garment in my studio that doesn't run through that machine — which is my American sensibility. I love couture because you can tuck it, catch it, it's gone. It's done. But through a machine, the equation has to be finished, flat, in order for it to go through that machine. With couture you can tuck and do all these …

MARY: You can keep working it.

ISABEL: Right.

MARY: Do you have a favorite machine? Who makes the best machines?

ISABEL: Oh my God …

MARY: I mean, are they getting better or are they getting worse?

ISABEL: I like the underwear machine. It's a cover-stitch machine with a stitch on the outside that looks like denim.

MARY: OK, so you kept going—how did you get back into retail again?

ISABEL: Barney's Uptown. Barney's was going to open uptown and said, "OK, we want to buy, to give you a space." And we said, "Look, you've got to bank on it."

MARY: You've got to pay us.

ISABEL: Up front.

MARY: Good for you.

ISABEL: Which is beyond rare. And that's how I survived. I get paid up front — half up front. And they've been wonderful, thank God. You know, with all their dealings, I still have my money and they've really been very supportive. They're interested in supporting people. And I'm not new. You've got to build, for heaven's sake, or who's going to be around?

MARY: Have you ever thought about going into accessories or shoes?

ISABEL: Oh, sure. I would love to.

MARY: What would you do first?

ISABEL: A good denim line. That's the first thing I'd do. Then shoes.

MARY: What about fragrance?

ISABEL: Oh, why do you think I'm building my name? I've always looked to being a house like Herms. That's my goal.

MARY: What fragrances do you wear now?

ISABEL: Chanel 22.

MARY: That's interesting. Not a lot of people wear that.

ISABEL: And Caron, the men's cologne. I wear a lot of 4711 and Vetiver. I remember when Todd [Oldham] was doing his fragrance and this mutual friend — Danilo, who does hair—would always come up to me and say "What are you wearing? What are you wearing?" He followed me for months. And I never told him it was Caron.

MARY: Do you feel like you're part of a community? Are you friends with other designers? You mentioned Todd Oldham.

ISABEL: Yes. And Marc.

MARY: Marc Jacobs?

ISABEL: Yes. Donna Karan. She leant me shoes for my shows before I went to Manolo Blahnik. She'd always lend me shoes. Geoffrey Beene always comes to the shows. It's a nice feeling. So yes, mostly a lot of other designers.

MARY: Have you found it hard being a woman designer? Does it make it any harder?

ISABEL: Yes. I create. Creativity, nowadays, has been left to men. Not women. In the '30s, yes — women. Look at the great designers then. Today, creativity has to come from men. We accept it from men. Not the women. Women designers are supposed to be sensible and just get you dressed and without a fuss.

MARY: Career dressing.

ISABEL: Career dressing. I'm not that.

MARY: So would you see yourself more like a Rei Kawakubo?

ISABEL: OK — She's easier to accept because she's avant garde. It has a label. I'm not avant garde. My American tradition is to be practical — which is what they're saying I'm not.

MARY: Well, you're very into practical details like aprons and pockets. It's like you're in your own little world — I shouldn't say little — an Isabel world.

ISABEL: What I do is from the heart. You have to feel it. There's a certain seriousness to it. That's why I'm not very fun. It's not fun. What I do kind of throws you off. It isn't your everyday garment. But yet, it's traditional. I do that by making you feel familiar with it. My aim is, once that garment is done, you look at it and you almost think you have it in your closet. You feel comfortable in it. I want to make a garment that lasts. It's not just yours. It should be your daughter's, eventually.

|

|

|

|

|

|

©

index magazine

Isabel Toledo by Annette Aurell, 1997 |

|

©

index magazine

Isabel Toledo by Annette Aurell, 1997 |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Copyright © 2008 index Magazine and index Worldwide. All rights reserved.

Site Design: Teddy Blanks. All photos by index photographers: Leeta Harding,

Richard Kern, David Ortega, Ryan McGinley, Terry Richardson, and Juergen Teller |

| |